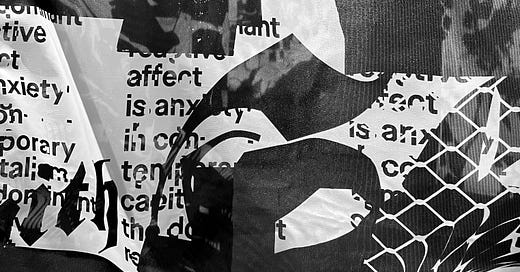

In a recent conversation with one of my students, I wanted to cite a quotation on typography that proclaimed “Type is the raw material of culture.” It’s one of those overly-simplistic, overly-broad, seemingly profound, and disciplinary self-congratulating statements, along the lines of Ellen Lupton’s “Typography is language made visible.” Yet, I kind of love these types of quotes for how in their simplicity they can offer up some complex ideas, whether or not they are objectively ‘true’. After a more or less extensive online search, I couldn’t find anything on this quote, so maybe I simply thought it up myself that day?

Claiming that type might be the raw material of culture evokes a line of thinking that finds its root in the classic philosophical tension in design between “form and content,” or in bauhausian terms “form and function.” Where does one end and the other begin? In Aesthetic Theory, Adorno states:

“Art negates the categorial determinations stamped on the empirical world and yet harbours what is empirically existing in its own substance. If art opposes the empirical through the element of form, (…) the mediation is to be sought in the recognition of aesthetic form as sedimented content. What are taken to be the purest forms can be traced back even in the smallest idiomatic detail to content.”

For Adorno, “artworks are something made.” Form is the result of the processes through which an artwork is made, and that making carries with it the social and economic relations of its particular historical and cultural juncture, its sedimented content. This thinking posits the essential thingness of the (art) object, reading its meaning in, and not through, its form. Form doesn’t follow content, it is content, just maybe not the content we are expecting. We might also think of McLuhan’s catchy slogan “The medium is the message.” In my essay ‘The Propaganda of Pantone’, I apply these ideas to colour, but perhaps it is even more relevant to typefaces.

Designers often understand typefaces as aesthetic objects in their own right, and/or as creative tools, as evidenced in by their current commodity form as licensed software. How does the claim of type as a raw material complicate our thinking?

A Note on the Type

The traditional colophon refers to a note at the end of a book that contains information such as the title of the work, name of the author and printer, illustration credits, typefaces and paper used, date and location of the printing, editioning information, etc. The term has its origin in the Greek, meaning ‘summit’ or ‘finishing stroke’. It could be thought of as a book’s signature (fine press editions were often signed and numbered by the author and printer on the colophon page), or the equivalent of a credit sequence at the end of a film. Though often written in a factual, historical, and informational tone, some colophons exhibited flourishes of poetry, perhaps tracing back to the fanciful book curses of medieval scribes.

In early printed books, the colophon was the only area where this bibliographic information appeared, serving an essential role for referencing and cataloguing in libraries and archives. With the introduction of the title page, standardized in the early 16th century, the author’s name, book title, and publisher’s mark moved to the front of the book. And with the advent of commercial trade publishing, other indexical information moved forward and overleaf onto what we now term the imprint or copyright page, listing all the legal information necessary to protect the work as a piece of intellectual property. This shift also marked the functional separation of the publisher from the printer.

With the book’s title and author, attributing the “creative” work within, and its publishing information, claiming the ownership of intangible rights, moved to the front matter, this left the humble colophon to finally address the material aspects of the book; the paper and ink of it, the metal pressed onto its surface, the means by which it is all bound together. It credits the designers and printers who worked with said materials and inscribes the time and place of the book’s production. The colophon thus makes explicit the implicit fact of the book as a material object, existing within the world and through the passage of time. It humbly acknowledges the collaborative labour and material origins of the book in counterpoint to individual authorial genius or claims to rights of exploitation and ownership. It expresses an ethics of craft.

The names, characteristics, and origin stories of the typefaces used hold a central place in the tradition of the colophon, at times complementing or replacing it entirely with a more specific “Note on the Type.”

A typical note might read:

This book was set on the Linotype in Janson, a recutting made direct from type cast in matrices made by Anton Janson some time between 1660 and 1687. This type is an excellent example of the influential and singularly sturdy Dutch types that prevailed in England prior to Caslon. It was from the Dutch types that Caslon developed his own incomparable designs.

As a young designer, and even now still, I was fascinated by these notes and learned a great deal from flipping to the back of a book, first. What does “singularly sturdy” type mean? And how is that a characteristic of the Dutch? What is a Linotype? Who’s this Caslon?

This book was set in a modern adaptation of a type designed by the first William Caslon (1692–1766). The Caslon face, an artistic, easily read type, has enjoyed more than two centuries of popularity in the United States. It is of interest to note that the first copies of the Declaration of Independence and the first paper currency distributed to the citizens of the newborn nation were printed in this typeface.

It certainly is of interest to note this! Typographic histories, tracing lineages and influences through countless ‘revivals’ across several centuries, run alongside technological, cultural, and political histories.

This book is set in a digitized version of Electra, designed by W.A. Dwiggins. This face cannot be classified as either modern or old-style. It is not based on any historical model, nor does it echo any particular period or style. It avoids the extreme contrasts between thick and thin elements that mark modern faces and attempts to give a feeling of fluidity, power, and speed.

Here Dwiggins, the American type designer, illustrator, and book designer, who is credited with popularizing the terrm “graphic design,” breaks with tradition and attempts to imbue his Electra with the feeling of fluidity, power, and speed. How do these feelings relate to the words being set in this book? And more broadly to the world in which they are written?

Some colophons note the point size of the type used and the amount of leading, a generous gift to train the designer’s eye. Others mention the paper used down to the origin of the mill in which it was made, hopefully softening our sense of touch. Common references to the means of printing and production, the type of presses used and the names of those doing the work, further the notion that the meaning of a book is informed not only by the textual content, but by the specifics of the labour involved. And other colophons might even include the weather during the season in which the book was made. In 1757, the scribe Shem’on included this note to the reader in the colophon of a Syriac manuscript copied in the city of Alqush, Iraq:

“In this year, people and cargo crossed over the Tigris River upon ice as if it were dry land for the duration of one month.”

The colophon, as a modest space to honour the material construction of the book, expands to archive a time and place in the world.

The colophon in my own book, Design Against Design reads:

The text of this book is set in Gramatika, a typeface designed by Roman Gornitsky, published by Typefaces of the Temporary State, and Stanley, designed by Ludovic Balland, published by Optimo. Where Gramatika paradoxically reinterprets Helvetica, Stanley draws inspiration from the classic Times New Roman. Under Balland's hand, it is imbued with a subtle iconoclasm through its sharp, angular, and at times, irregular forms. As Balland states, “a font is there not only to be read, but to keep a visual memory of things.” Folios are set in Youth Grotesque by Feedtype and image captions are set in Syne Tactile by Bonjour Monde and Lucas Descroix.

This book was printed and bound by Printon AS in Talinn, Estonia, using Olin Design Nordic White and Cordenons Bohème papers, in an edition of 2000 copies. The book was designed in Montréal/Tiohtià:ke in so-called Canada by LOKI and published by Set Margins' in Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

The work was completed under the snowy skies of the last days of 2023, while bombs rained down on Gaza, and the people of the world mobilised and resisted in solidarity.

The colophon points us back to Adorno’s theory of sedimented content. They are the last words we read as we contemplate the end of a story that might leave us wanting more. A bridge taking us back from the imagined landscape of the text to the material reality of our own lives, the temperature of the room around us, the news on the radio, the list of tasks yet to be done.

For more, read Praise the Colophon: Twenty Notes on Type

With thanks to Juliette Duhé for our conversation on the corner of Parc and St. Viateur that helped me pull these thoughts together.